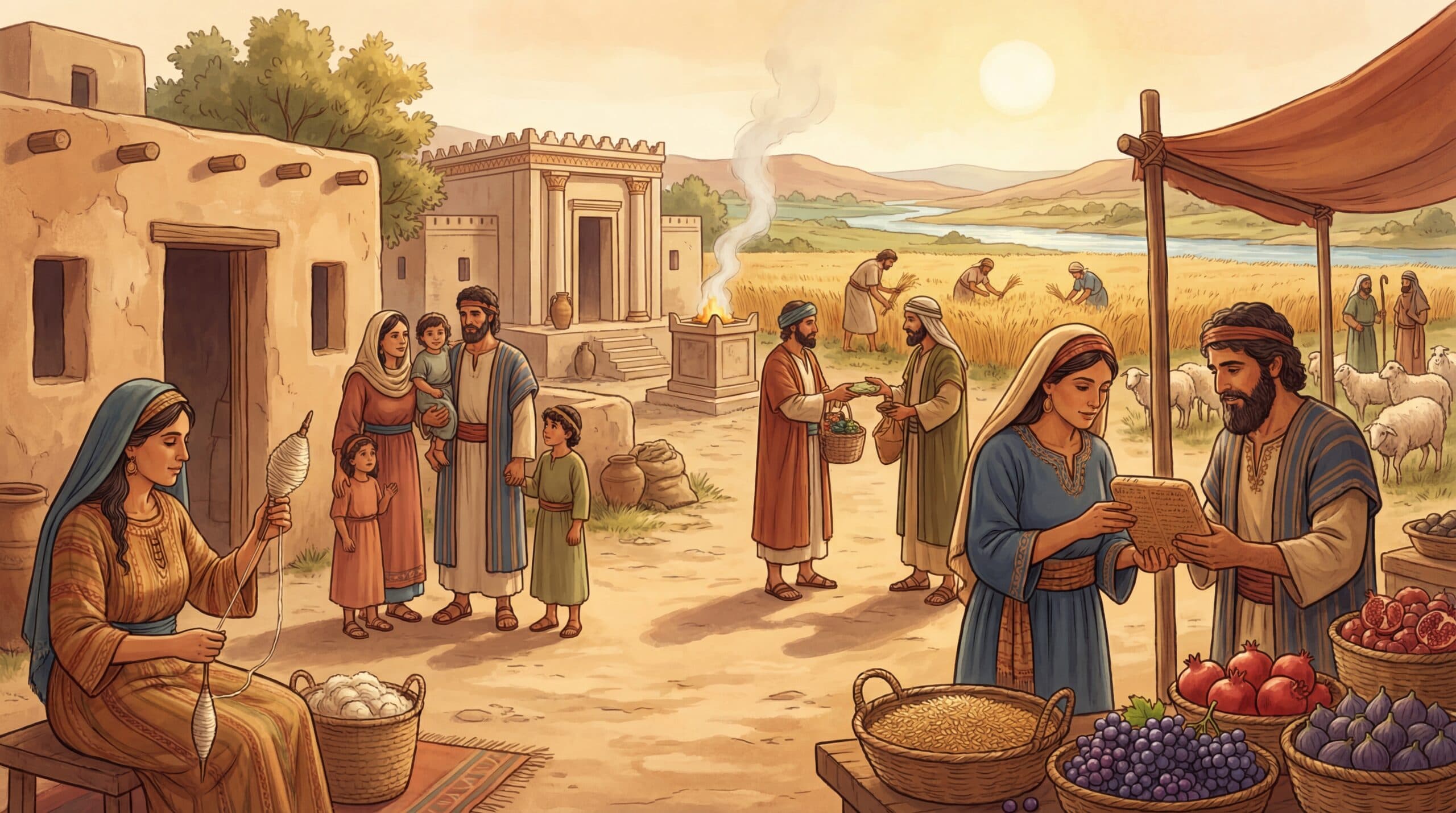

Society & Economy

Among the spiritual habits of the Arameans, particularly the Festivals and Holy Times, a remarkable principle can be recognized: The social order was not primarily determined by the work performed. Craftsmen, merchants, farmers, or administrative officials each had their fixed roles. In this Aramean society, the value of a person was determined just as strongly by their relationships, their abilities, and their responsibility within the community as it was by their occupation.

Family formed the heart of the social structure. Structures shaped by inheritance law often determined economic obligations and the distribution of resources. Women actively participated in economic life, trading or managing possessions, as impressively evidenced by a “Clay Tablet” documenting a woman in business affairs. Even outside the family, personal relationships, guarantees, and confirmation by witnesses played a central role: They provided legal and social legitimacy to economic transactions. Loans were granted, agricultural production was monitored, and moral concepts permeated every level of trade. Honesty, adherence to contracts, and the fulfillment of social duties were considered divinely approved and secured the trust that formed the foundation of the community.

Religion was omnipresent in this structure. Temples and priesthoods functioned not only as spiritual centers but also as economic actors. They controlled supplies, coordinated the distribution of goods, and influenced trade and production. In this interplay of faith, law, and economy, norms were conveyed not only through laws but through the concept of divine order, an invisible network that guided daily actions.

Despite regional differences, Aramean society was connected by a dense network of kinship, economic dependence, and religious order. What was noteworthy about this was that this network did not stop at local borders; rather, kinship ties often extended across multiple Aramean kingdoms. This far-reaching network provided stability, allowed for cooperation across generations, and conveyed a sense of security and community to the people. Every citizen was integrated into a world where social relationships, responsibility, and faith were inextricably intertwined. A society that lived, functioned, and preserved its identity for centuries.

The Social Status of Women

The inscriptions from Sefire and Tell Fekheriye suggest that typical female activities primarily included the care of small children and baking bread. A Phoenician-Luwian inscription from Karatepe depicts a woman walking alone with her spindles as a symbol of peace and security—an indication that spinning was also a classic female activity, as evidenced by archaeological finds at Aramean settlements.

Social status and functions allowed women of the higher classes to participate in public offices and financial undertakings. For example, Naqi’a Zakutu, the influential Aramean wife of Sennacherib, was a queen and later queen mother, while her sister Adrami and daughter Saditu were also prominent.

The legal status of women in Aramean society is primarily evident in marriage contracts. In these, the woman was not simply a ‘slave girl’ or the daughter of an impoverished freeman, as was often the case among neighboring folk groups, but frequently an equal partner. Several Egypto-Aramaic documents from the Persian period attest to this, in which the woman is treated as an independent partner with her own rights after the marriage.

Naturally, written marriage contracts presuppose an upper class or at least a more affluent middle class, while most marriages were concluded verbally. However, later evidence shows that even common women in the Near East retained relative legal freedom through verbal agreements before witnesses and corresponding property regulations—in contrast to the usual practices in the Greek and Roman world.

A Greek divorce document from Dura Europos, dated to 204 CE, concerns two Aramean villagers and explicitly states that “they had previously been married by verbal agreement.” The woman appears in this document as an equal partner, with each party authorizing the other to remarry and waiving all claims.

Labor Concept and Economic Status

Generally, the Aramean way of thinking in the 8th century BC held that a person’s labor power was separate from their person. There are six documents reporting that debtors had to settle their debts partly through labor. It could be sold or lent without changing the worker’s social status or subjecting them personally to an employer. This is particularly evident in agriculture, where the demand for labor fluctuated strongly from month to month.

An illustrative example is provided by a labor contract from the Kingdom of “Bit-Bahiani,” concluded towards the end of the 7th century BCE. Five workers committed themselves for the harvest season. As wages, the foreman received four white sheep in advance on behalf of the family from their employer, ‘SehmiirI’, which were presumably managed by the family members of the reapers themselves. In this way, the contract elegantly combined economic necessity, family responsibility, and the flexible use of labor.

A proverb by Ahiqar, an Aramean philosopher dating back to the 7th century, states:

‘’l y’mr ‘tyr’ b ‘try hdyr ‘nh’

“The rich man should not say: ‘Because of my wealth I am venerable [or honorable]

Furthermore, in the Aramean way of thinking, the difference between an employee and an employer did not mean that one had to work while the other could live without work. In the Aramean world, the need to work was not a criterion used to distinguish between the rich and the poor. On the contrary: In Aramean literature, God himself is depicted as working, while idle gods are destined for downfall.

The Diet of the Ancient Aramean Population

The diet of the ancient Aramean population was balanced and largely based on grains and fruits, while meat was only served on festive occasions, as it was considered a luxury. Barley was particularly important, serving as the staple food. Considering parallels from better-documented Babylonian sources, it can be assumed that barley was sometimes in higher demand and even more expensive than dates. Among the fruits, grapes, pears, dates, olives, pomegranates, and figs played a central role in daily life. Meat was always an exception, even among livestock breeders, who mainly kept sheep for milk and wool. Legumes such as lentils and peas, as well as various vegetables, supplemented the diet. Herbs and spices like coriander, dill, and mint provided flavor, while eggs, wine & beer, and honey rounded out the spectrum. Fish was caught on the Mediterranean coast as well as in rivers like the Euphrates and the Orontes. This diversity reflects not only dietary habits but also social and economic structures: grains and fruits formed the basis, while meat, wine, and honey were symbolic of festive occasions and accompanied religious rituals. In this way, diet, culture, and faith connected the people and shaped their daily lives in the Aramean communities.