The Mighty Weapon: Aramaic

In daily life, people usually traded directly with each other. For such simple transactions, no merchants were needed — everyone knew what they wanted to give and what they would receive in return. However, once the view extended beyond one's own city walls, things became more complicated. The major international trade connections that developed in the late second and early first millennium BCE in the Near East required specialists: people who knew distances, routes, risks, and prices. This is where the Arameans primarily stepped in, as they knew the political relationships between the countries like hardly any other people.

Aramaic, the language of the Arameans, became their most powerful tool in this dynamic environment. It greatly helped trade across national borders and thus developed into the very first major trade language in the entire Near East. Within a very short time, Aramaic advanced to become the Lingua franca of the region.

Its simple structure and wide use by Aramean merchants made it an essential link between peoples who spoke different native languages. Whether in Egyptian trading offices, Babylonian palaces, or Persian administrative centers — Aramaic enabled smooth communication and standardized business processes. It was this universal acceptance that sealed the language's triumph and made it the dominant vehicular language of the Ancient Orient for many centuries.

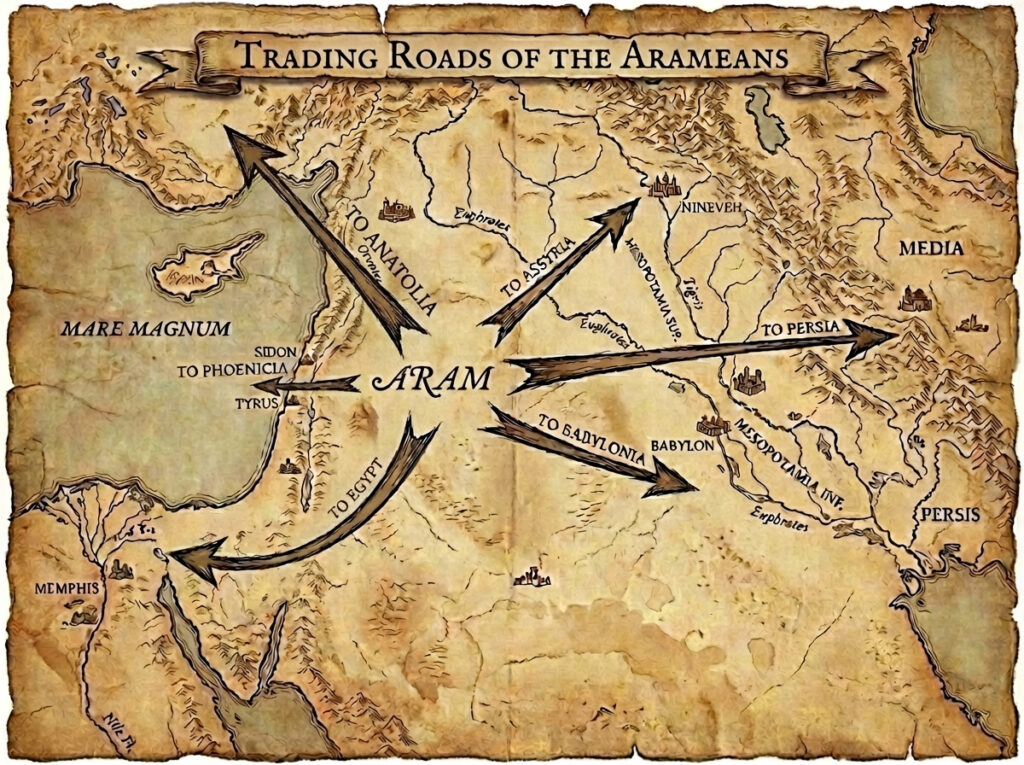

Trade Routes

Between Phoenicia and Assyria, as well as from the Persian Gulf across Babylonia to the Mediterranean, trade routes developed that bridged great distances. These paths were vital for the exchange of luxury goods such as frankincense, spices, precious metals, and textiles. Caravans, often utilizing camels, utilized dry desert paths for swifter travel. While others chose the longer but safer route along the Euphrates or the Tigris rivers. On the river, where barges and boats were used, boats significantly facilitated the transport of metal and other heavy goods compared to the land route, highlighting the economic efficiency of these waterways. Despite these far-reaching trade networks, the Aramean trade seemed surprisingly difficult to grasp in detail. Aside from isolated documents from the 7th century BCE mentioning sales of barley and straw, many sources remained silent. However, only a look at the Hermoupolis Papyri gives a livelier impression: they report from the late 6th century BCE, when Aramean peddlers from Syene (Aswan) moved through the cities, offered goods, haggled, and went wherever buyers could be found.

Merchants and their Reputation

Several merchants with typically Aramean names appear in documents from the 7th century BCE, such as Ḫadafaʿ and Bir-Šamaš, Raʾīm-Adad, Il-idri and Aḫī-qām, a merchant from the king's staff, thus "a king's merchant." In another document, a merchant is named in the census of the district of Ḫarran, and a record of the transactions of merchants in the city of Ḫarran explicitly mentions: "2 linen garments, bought for 1 mina 23 shekels from a certain Aramean." According to a petition addressed to the king, merchants had a rather bad reputation: "May my people not die in the house of the merchant!", writes the sender of the letter. The traders were reputed to sell stolen goods. This is evidenced by a letter of recommendation to the elders of the Jewish community in Elephantine at the end of the 5th century BCE, in which a man accused of theft reports about a 'dyer's stone that they found stolen in the hand of the merchants'.

The Story of Batay

According to a surviving clay tablet, a small but insightful glimpse into the everyday life and administrative practice of the Arameans can be gained.

The story begins with Harranay – Hrny –, the son and probably successor of an administrator in the palace of the queen mother from the region of Aram-Nahrain, who is likely still in training, responsible for the management of the palace’s venerable granaries. The borrower was an Aramean woman named Batay – 'Ba-ta-ia-a', as she was recorded in writing there. Her name also appears in an older document from the same archive, suggesting that the lady was not unknown in the community near the palace. Despite the rather modest amount of barley – and perhaps, one might assume, because she was in debt or was a woman – she needed a guarantor: a certain Bar-Samas, who, in generous readiness to help, vouched for her. This is recorded on the tablet by the Aramaic expression 'mh' yd'

To confirm the loan, four witnesses also appeared – apparently, even with small quantities, people were not willing to leave fate entirely to the goodwill of those involved. An interest rate is not mentioned; be it out of generosity, forgotten diligence during inscription – or because no one could have imagined that a little barley would one day go down in history.

The Aramean Currency

The words 'aklū' and 'bubbūrū' seem to denote standardized silver ingots, meaning the designation corresponded to the value and thus also the corresponding weight of the coin. The use of terms that actually denote bread to designate silver weights is also attested in Hebrew: thus ‘kikkiir’ can denote both a large loaf of bread and a silver ingot of sixty minas. An official standardization of the silver ingots is evidenced by the Sam’alian silver ingots with the name of King Bar-Rakkab as well as by an inscribed silver fragment from the treasure of Nush-i Jan (Iran), dated to the 7th century BCE. Depending on the region and inscription, the ingots weighed 8.5g, 14g, 20g and up to 500g silver ingots. The Arameans appear to have played an important role in the standardization of weights and silver ingots in the Near East, whereby other peoples adopted this system and later further developed it.

Two Aramaic formulas appear to characterize the weight systems: ‘b zy ’rq’, according to “weight, (name) of the land,” and ‘mnh zy mlk’ “weight, (name) of the king.”

Luxury Goods: Made in Aram

Furniture decorated with ivory can be traced back as early as the 9th century BCE in Bit-Zamani, in the 8th century BCE in Bit-Agusi, and in Aram-Damascus furniture was even decorated with gold and silver.

Silverwork and golden weapons were available in Bit-Adini. Furthermore, many peoples from Anatolia could acquire ivory carvings from elephant tusks there.

The Nimrud ivories with the inscriptions Lʾš and Ḥmt prove that ivory-decorated furniture was also produced in the Aramean kingdom Hamath.

The evidence regarding the use of ivory provides exciting insights into the spread, domestication, and possible breeding of the West Asian elephant, especially in Hamath, Aram-Damascus and Bit-Adini.

Since most of these centers were characterized by Aramaic culture in the 1st millennium BCE, ivory production must be considered an Aramean craft – Edward Lipiński

Among the Aramean export goods were apparently also precious stones. A single piece of written evidence points to this: an administrative text from Mari that mentions a deep blue stone with the Aramaic name “Rʾimatum Zagin.” The described gemstone could originally have been lapis lazuli; however, a sapphire, whose color spectrum ranges from pale to deep indigo blue, or chalcedony, which was often used in Aramaic seal engravings, is more likely.

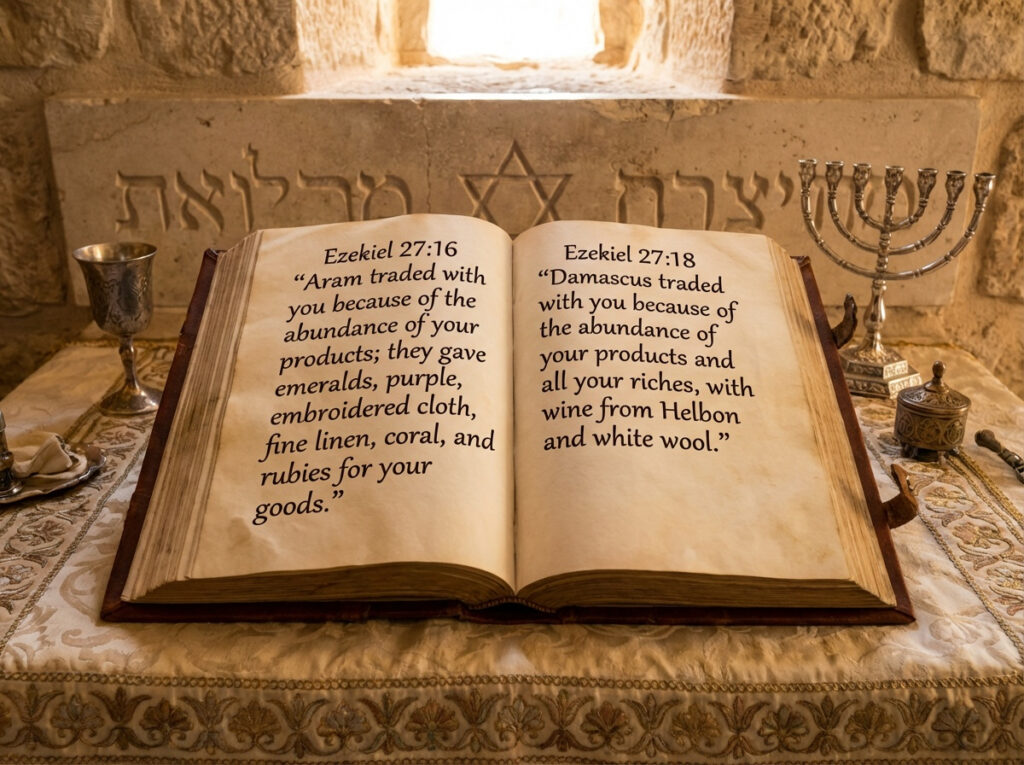

Furthermore, in the Bible – particularly in the Book of Ezekiel – colorful fabrics, fine linen, corals, rubies, and other precious stones are mentioned as trade goods with which the Phoenicians traded with Aram.

When it comes to clothing, we turn to the purple dyeing of wool with murex snails. This was only possible on the Mediterranean coast – in Hama and in the kingdom Aram-Damascus, but especially in Phoenicia, modern-day Lebanon.

However, the use of murex snails was not strictly necessary, as plant-based dyes could replace them.

A locally produced, red-dyed wool textile is mentioned in the Phoenician inscription of Kilamuwa. The Aramean King Kilamuwa from Bit-Gabbari, who lived in the second half of the 9th century BCE, boasts in it of having concluded a clever trade agreement. In the context of the Kilamuwa inscription, however, one should think less of costly purple, but rather of a more affordable, red-dyed woolen garment that was nevertheless valuable enough to act as a bartering good in a political agreement.

Aramean Production

Based on trade and tribute payments, it is possible to roughly reconstruct which countries were known for their production and their goods:

Bit-Adini: Gold, silver, tin, bronze, bronze casseroles, linen garments with multi-colored embellishments, cedar beams, ivory furniture, ivory dishes, gold jewelry, gold daggers, oxen, sheep, wines, chariots, monkeys, horses, weapons, ivory

Bit-Halupe: Silver, gold, bronze, iron, tin, bronze casseroles, bronze pans, bronze buckets, much bronze property, Gisnugallu Alabaster, decorated plates, garments with multi-colored embellishments, linen garments, fine oil, cedars, fine aromatic plants, cedar shavings, purple wool, red-violet wool, wagons, oxen, sheep

Bit-Agusi: Gold, silver, tin, iron, bronze, oxen, sheep, linen garments with multi-colored embellishments, horses, wine, gold as well as silver beds in the palace.

Bit-Gabbari: Silver, copper, iron, linen garments with multi-colored embellishments, oxen, sheep, cedar beams and resins

Hamath: Wagons, weapons, copper, gold, silver and bronze vessels, precious stones, ivory, boats,

Aram-Damascus: Wagons, weapons, boats, gold, silver, bronze, tin, diverse precious stones, ivory furniture, stone production, copper, cedar and pine resin, oil, camel breeding farms, ostrich pens, wines

Bit Bahiani and Bit Asalli: Gold, Silver, Tin, Bronze, Bronze Casseroles, Oxen, Sheep, Horses, harnessed Chariots

The Rise of the Arameans at the End of the 2nd Millennium BCE Department of History and Cultural Studies, Institute for Near Eastern Archaeology, Freie Universität Berlin

THE ARAMAEANS THEIR ANCIENT HISTORY,

CULTURE, RELIGION Departement Oosterse Studies Leuven - Paris - Sterling, Virginia

Department of Oriental and Slavonic studies, Katholieke Universiteit Leuven,